He's Dead Jim: Why Perfection in Design Isn't Perfect

2018 was a benchmark year for me in understanding design at its quintessential level. I took up new roles as a design lead in both my career and in my extracurricular pursuits. Both taught me important lessons in managing a design product’s lifecycle.

Spoiler alert, the Perfect Brew ended up being anything but perfect in the end. Despite releasing an MVP early this year, it was almost a complete failure in terms of meeting initial goals and expectations… but hey, that’s ok. Here’s a documentation on why this project was doomed for failure since its inception, and what I’ve learned from it as a result.

Design is about creation, not just process

My purpose for starting the Perfect Brew was out of a starry-eyed naivety to master the design process. As quoted from my first article in this series,

It wasn’t long before I realized I wasn’t very close to the design work I had imagined I would be doing out of college. That’s normal, of course. The real world of “UX” can be a little messy. There are technical limitations, business-defined timelines, and more unpredictable barriers that can impede a utopian UX gameplan. After spending nearly half a year re-reading and annotating the UX Book by Dr. Rex Hartson I wondered if I would ever get an opportunity to test out the many activities documented in it. And so, I got a crazy idea. Let’s start a digital project that puts the user first. Let’s start a project with realistic deadlines and the full UX cycle from ethnographic inquiry to wireframe iterations and post-analytics.

When I started the year, I was only focused on applying academic knowledge in real world situations. My first notable failure occurred in March when I had the reckless ambition to push for process perfection in the Perfect Brew by putting together a WAAD for a simple domain of work. Ironically my pursuit for perfection became my biggest shortcoming as I was quick to realize that the rigor of academia I wished to apply did not fit the mold of the domain fidelity of work I was designing for. The value produced by the effort was noticeably lackluster, but more importantly I did not efficiently use the time and energy of my team appropriately as a project manager. Instead, I had mistakenly placed my focus strictly on the process in hopes that it would create a better final product.

I’ve learned that it is ironic to believe that a “utopian UX gameplan” can exist because design is fundamentally not utopian. Before being perfect, design must be practical. Design has an objective goal to create; therefore constraints, limitations, and timelines must be accounted for in the process in order for users to be able to use the product at all in the first place. With that in mind, it is foolish to treat academic guidelines as laws. Guidelines are meant to be applied after first considering the context of work; only then can a product be realistically made tangible and ultimately usable.

As a manager it became more apparent to me the importance of a delivered product as opposed to a "perfect" one. More importantly, from the lens of a designer, I realized that no product can even be perfect unless it is usable to begin with.

Shorter and faster is sometimes better

Throughout the year, my boss would often ask me to consider how many valuable ‘aha’ moments I would realistically achieve through an extended and expensive discovery phase. He reasoned that most projects, unless they are significantly domain complex, would not have anything that could not be reasonably anticipated by an experienced designer.

I was incredibly skeptical of this statement until the Perfect Brew came to a crashing halt in late June. As a result of the needless rigor, our team was becoming exhausted. Many of us lacked the time or commitment to match the outlined strategic goals; it also didn’t help that our hyperextended efforts rarely produced anything marginally more valuable. In fact, many of the ‘aha’ moments of this project came more during testing than discovery.

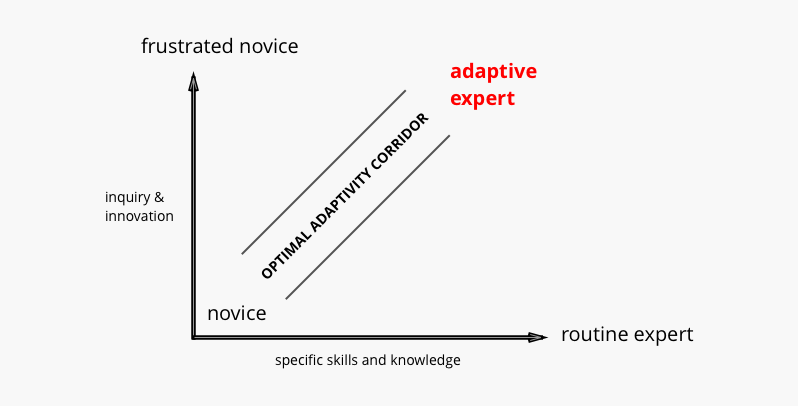

Often our first instinct as UX designers is to request for a comfortable and extended discovery period in order to ensure that we are creating a foolproof user-centric product through the data-driven model of contextual inquiry. Realistically though, this is often inefficient and impractical. Bransford coins this as being a “frustrated novice” where the designer does not rely on specific skills or knowledge to routinely approach projects. Designers, as Bransford argues, should instead aim to be “adaptive experts” who are able to reactively formulate new cognitive models and make new meaning from which to take action with discipline.1 In other words, it means being able to respond and make solutions to the context of work appropriately and efficiently.

In the case of the Perfect Brew, that would have meant foregoing an extended discovery phase in favor for a more startup based a la Eric Ries validated learning approach. Since understanding café customers falls under a relatively simple domain, it would have been more practical to spend more time creating and testing as opposed to research. This would have allowed for earlier problem detection and a faster release schedule; had this been a real project, it would have also meant less cost.

Conclusion

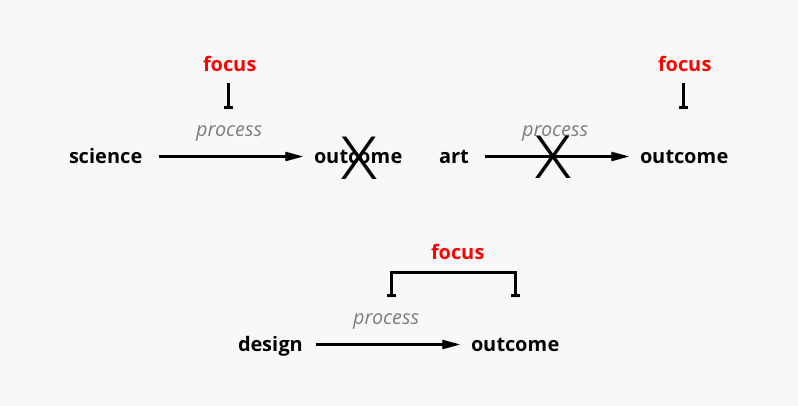

To most veteran designers, the title of this article is an obvious statement. There is no such thing as a “perfect” process in design, because design is a contextually founded and creative pursuit. Unlike scientific inquiry, which is focused on describing and explaining things that already exist, designing is the means by which desired ends become real.2 In other words, while perfection can be arguably found through a focus on process in science to uncover things that already exist, it can’t be found in design because design is quintessentially creation. Given the limitless number of creative possibilities, perfection cannot feasibly exist.

Ultimately, the key takeaway of this series of thought is that since design cannot be perfect, there will inevitably be diminishing returns on the rigor of process against the time of completion of a tangible product. To ensure the success of a released product, always consider the context first.

The Perfect Brew, if anything, was the perfect failure- it turned out to be one of my greatest lessons in design and product management. I look forward to failing even bigger in 2019 :)

References

- Bransford, John. 2010. Adaptive People and Adaptive Systems: Issues of Learning and Design.

- Nelson, Harold. 2012. the design way.